There is much excitement and speculation about the use of hydrogen as a greener fuel of the future. It is true that hydrogen does not produce greenhouse gases when burned and produces more energy than gasoline, however the challenges of working with hydrogen are significant and often simplified or even overlooked.

Hydrogen can become explosive in the atmosphere at between 4% and 75%, making it one of the most explosive gases in industry and a big hazard when leaking. Moreover, Hydrogen is odourless, colourless and non-toxic, making it hard to decipher whether it has escaped or not through mere touch, taste or smell. This is its sleight of hand! Hydrogen is the smallest occurring molecule in nature, a molecule of gasoline is typically fifty times larger than that of hydrogen, and this is where the trouble starts.

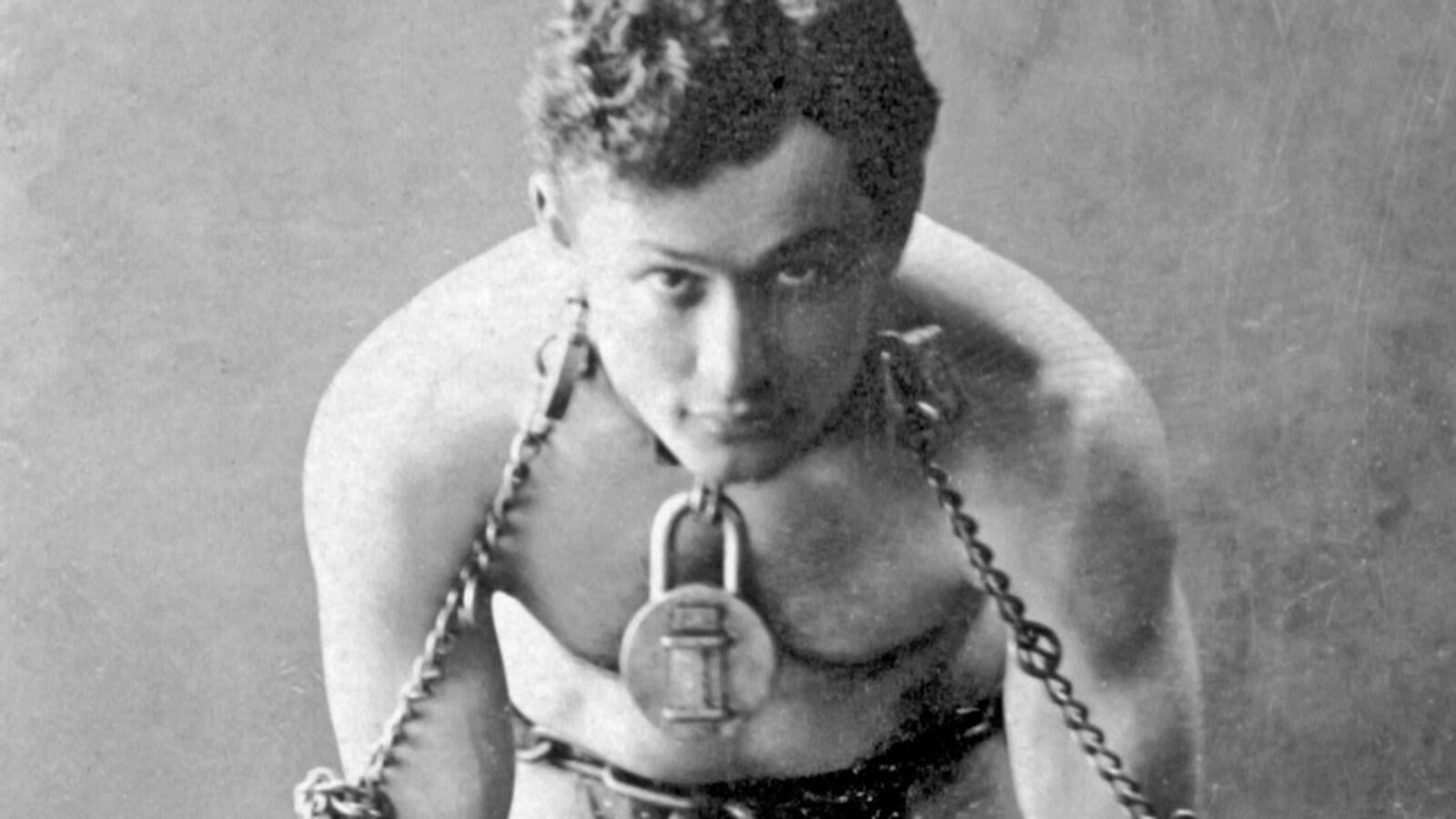

The fact that hydrogen is physically so small makes it much harder to contain. It escapes more often than Harry Houdini, and when it does, the fact that it is so explosive is a real problem. The idea that the existing infrastructure for vehicles, such as petrol stations and pumps, can be switched out to provide an outline for storing and dispensing hydrogen is much harder than it at first appears. Hydrogen can not only creep through the smallest of apertures but can penetrate the crystal structure of solid metal. This embrittles the metal making it more vulnerable to fracture. This means expensive and heavy high-pressure tanks are needed to contain it.

It has been suggested that hydorgen could actually be stored inside the crystalline structure of some metals, but even inside a metal hydrogen diffusses very quickly because of its small size, meaning it is difficult to know how much is inside, where it entered and where it might re-appear.

Therefore, with the ever-changing world leaning more towards greener alternatives to fossil fuels, and Hydrogen leading the charge for it, controlling Hydrogen leaks is essential.

Unlike Harry Houdini, the escaping of Hydrogen can be mitigated with the correct procedures and equipment, but this is not straightforward and having suitable detection systems to alert against a hydorgen leak will become commonplace if hydrogen does become as ubiquitous as many believe it will.

A site risk assessment will mitigate the danger to personnel if a leak occurs and complementary gas detection technology will further benefit the safe running of any plant or building where hydrogen is being used or stored. Without these careful controls, the escape artist that hydrogen undoubtable is, will be free in one bound or less.